International Defense Conference and IDEX 2019 Review

Over the seven days of 14 – 21 February, Abu Dhabi played host to two events that brought together global thought leaders, senior military and defense community leaders, industry executives, and hundreds of defense and security industry companies from across the region and throughout the world.

The International Defense Conference (IDC) 2019 was held on 14 and 16 February with a focus on assessing the economic, defense, and security implications of the Fourth Industrial Revolution (4IR). The event included an impressive line-up of international experts, ranging from theoretical physicist Michio Kaku of City College and the City University of New York to defense industry CEOs and senior executives (for example the CEOs of Thales, Tawazun Economic Council, Naval Group, and Saudi Arabia Military Industries all appeared on panels), to military leaders, such as General Joseph Votel, the Commanding General of the U.S. Central Command.

IDC 2019 served as both a stand-alone event and a lead-in for the biennial International Defense Exhibition (IDEX). IDEX is among the most well-attended shows in the world, given the importance of the United Arab Emirates (UAE) and, more broadly, Arabian Gulf defense markets. According to Jane’s Defence Industry and Budgets’ recently-released Global Balance of Trade report, Saudi Arabia is the largest export market in the world in terms of the value of goods delivered annually. The UAE and Qatar are both in the top ten. Overall, the Gulf export market constitutes about one-third of all defense exports by value delivered on an annualized basis. The importance of the Middle East and North Africa market has grown over the last several years, despite drops in oil prices and expensive efforts in several countries to diversify economies away from the energy sector.

Together, these two events provided considerable insight into many of the trends, drivers, and critical uncertainties shaping the future of the global defense industry in transition.

The Fourth Industrial Revolution

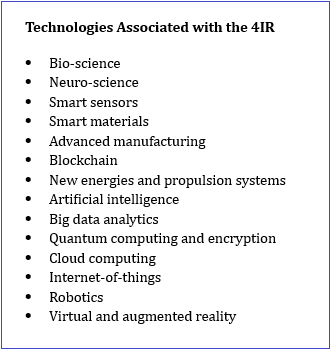

The Fourth Industrial Revolution (4IR) is near the top of the list of transformational forces driving changes to the defense industry. 4IR refers to the global systematic innovation and development efforts in a wide-range of emerging technologies designed largely to connect the physical and cyber worlds, according to Klaus Schwab the founder of the World Economic Forum (see text box to the right for specific technologies generally associated with the 4IR). Or, as Professor Kaku said during IDC 2019, the main output of the 4IR will be digitization of industry, society, and, potentially even humans themselves.

The world is just at the start of the 4IR, even if several industries are beginning to experience early effects of the deployment of 4IR technologies, especially in the media and telecoms, finance, automotive, transportation, and medicine and health industries.

4IR innovation is generally viewed as emanating mostly from the commercial hi-tech and information, communications, and telecommunications industry or applied research institutes. But most of the technologies and capabilities these technologies enable are dual-use, meaning that with only subtle technical adjustments and/or novel operational concepts they are also highly – relevant in a defense and national security context as well. And as militaries increasingly prioritize these technologies and the capabilities they can deliver, the global defense industry is also investing in innovation in these technologies. They are also trying both to compete and collaborate with high-tech companies to meet this demand, further revealing the intersections and implications related to the 4IR and defense. Two implications in particular stood out at IDC and IDEX.

First, the commercial development and dual-use nature of many 4IR technologies eases the pathways of diffusion of disruptive capabilities enabled by 4IR technologies. As a result, more actors will have the capacity to disrupt strategic and operational environments. Daesh’s use of small drones for both surveillance and strike is a useful example. So, too, is Russia’s use of social media to undermine political, social, and economic systems in the United States, Western Europe, and in former Soviet states.

This intersection of commercially available and easily diffused 4IR technologies and the information / cyber domain is particularly concerning for defense and security planners. Threats in this area can be exceptionally difficult to detect, attribute, and deter through the traditional means of “military / technological overmatch.” In a November 2018 report entitled ‘Weapons of the Weak’, Brookings Institution researcher Alina Polyakova outlined the ways in which improvements in easily diffused AI applications such as deep learning, facial, voice, and emotion recognition and mapping software, and natural language processing can combine to create compelling and strategically affecting “deep fakes” or “synthetic news content”. This content can, in turn, be used to shape perceptions and behaviors, exploit divisions, or even extract sensitive information from targeted individuals who are frequently completely unaware of their manipulation.

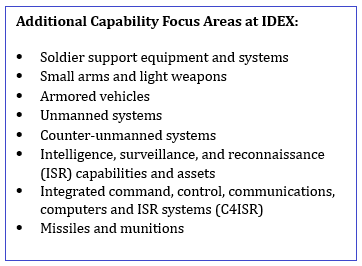

Second, military and security capability requirements are now incorporating 4IR technologies both to improve traditional capabilities—planes, tanks, ships, missiles, weapons—and also to, in the famous words of hockey great Wayne Gretzky, skate to where the puck is going to be; that is, to develop entirely new types of artificially – intelligent enabled capabilities— networked drone swarms, for example, or artificially-infused border guards — that will change the way that military and security communities think about, prepare for, and carry out their missions.

The emerging importance of AI to the future of intelligence, surveillance, reconnaissance (ISR), cyber-conflict, and combat was highlighted during IDC 2019 during a panel on Innovation and the Era of Cognitive Warfare. SAAB Deputy CEO Michael Johannsen noted that “Cognitive warfare is already everywhere, even before we begin to think about drone swarms and combat,” citing development in smart radars and sensors and cognitive electronic warfare (EW) that will create powerful capabilities to autonomously adapt to environments and threats.

The state of play of current and emerging efforts to infuse novel applications of AI into defense and security capabilities was very much on display at IDEX. Multiple companies—particularly from Israel and China—marketed facial recognition systems and machine-learning enabled data collection and processing systems designed to carry out domestic surveillance or possibly identify and help interdict terrorists. The images to the left are of systems marketed by Poly Group, one of China’s defense industrial base state-owned enterprises. These capabilities have broad applications, but concern in the United States, in particular, has emerged about China’s ability to export “techno-authoritarianism” buttressed by these technologies. In addition, concerns over increased cyber-risks associated with the collecting of more sensitive personal data were realized in February 2019 when Dutch cyber-reseracher revealed that Chinese facial recognition company SenseNets accidentally released a database with facial recognition and other personal data collected through their software’s use in China.

Ultimately, IDC and IDEX both revealed that the 4IR is bringing tremendous new opportunities for industry and security and defense communities, even if much of the discussion to date has focused on challenges. Stakeholders in industry and government capable of 1) adopting more risk-tolerant approaches to innovation; 2) partnering with, acquiring, or funding non-traditional defense companies; and 3) introducing and adapting new manufacturing techniques and procurement models will have a competitive advantage in the crowded defense market of the future.

A New Approach to Defense Offset

Many export market governments have, over the last two decades put in place policies and programs designed to “offset” the costs of large defense procurements awarded to foreign contractors. Through these programs, defense contractors are typically required to transfer technology, provide workshare or joint and co-development of platforms and systems to local industry, or train the local workforce in part to help develop local defense industry capabilities and to generate benefits for the broader economy.

Offset programs have achieved inconsistent results over the last two decades. Mixed in with success stories of co-development projects are a growing number of failed and unsustainable projects that demonstrate the insufficiencies of the transactional approaches taken by defense contractors and procuring governments. More fundamentally, challenges in offset project delivery reflects the misaligned objectives between procuring governments—building a local defense industry and deriving long-term economic benefits—and foreign defense contractors that prioritize-revenue, margin, and reducing risks of failed delivery.

However, changes are coming to the complicated and sometimes frustrating world of defense offset. During the lead-up to IDEX 2019, the UAE released a new offset policy called the Tawazun Economic Programme (named for Tawazun Economic Council, the organization within UAE that designs and implements offsets programs). The policy was notable for actually implementing many of the recommended best practices being discussed by defense contractors and importers around the world as means of establishing the sort of long-term partnerships between government and industry and sustainable offset programs that meet the needs of all stakeholders. Key plan concepts included: shared risk and investment in local workforce skills development; proactive communication of offset priorities by the UAE government; reduction in penalties for offset non-compliance; and a focus on increasing flexibility of offset programs. Interviews with multiple defense industry executives at IDEX revealed an initial optimism and enthusiasm about the concepts in the new policy mixed with general caveats about how this more proactive and strategic approach will be implemented.

A Global Arms Bazaar

Defense offsets are a persistent component of the global defense market largely because export markets have gained more leverage in the post-2008 financial crisis budget environment. According to Jane’s, in 2005 U.S. and NATO spending constituted nearly 67% of global spending on defense. In 2018, it constituted just over 50%. Western and Russian defense companies have chased this budget shift to the south and east, creating opportunities over much of the 2010s for export markets to demand technology, workshare, skills development, and co-development through offset. In addition, as more states have focused on developing indigenous defense industrial bases, the global defense market landscape has seen the entry of more competitors, especially in emerging or “good enough” export markets that do not necessarily need the world’s most advanced military equipment to meet all of their requirements.

To be sure, the United States is still, by far, the largest defense exporter in the world, with over three times as many exports in terms of value of equipment delivered annually as Russia (#2) and an even more pronounced gap over third-place France. Traditional providers Germany, Italy, the United Kingdom, Sweden, and Israel take up the next few slots in various orders depending on the year.

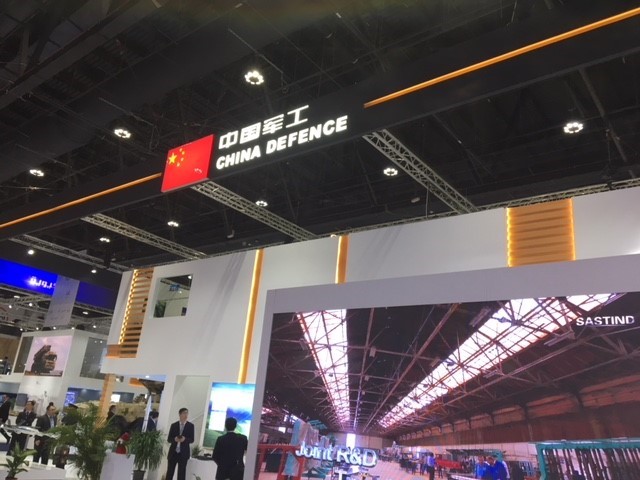

What has been notable, especially in the highly competitive market of the Gulf and Middle East, is the growing presence of the domestic defense industry of China and other emerging market providers from Eastern Europe, Asia, and even from across the region. IDEX had notable representation of industry from, among others, the Republic of Korea, Egypt, Saudi Arabia, UAE, and Eastern European states. Even Sudan—which does not have a mature defense industry—had a presence at IDEX in hopes of capitalizing on one of the world’s truly global arms bazaars.

China, in particular, has had recent success in building an export portfolio in the region, especially in the unmanned systems market. A December 2018 report from British think tank Royal United Services Institute (RUSI) highlighted the extent of China’s sale of armed drones to the Middle East including to UAE, Jordan, Iraq, and Saudi Arabia. The sale to Saudi Arabia includes a deal for armed CH-4 drones to be produced in Saudi Arabia.

Part of the opportunity for China is that the United States has, to date, prohibited the sale of armed drones due to fear of proliferation of these deadly and advanced technologies. As an Indonesian government official noted in late 2017 after announcing an agreement to buy armed drones from China “Only China can sell the drones to us and the others cannot.” The current U.S. administration took steps in early 2018 to better understand and delineate the conditions under which U.S. companies could export armed drones largely to offer some support of U.S. industry as it seeks to deal with new competitive dynamics and requirements in a changed and still changing global defense industry and market.