Repo, SOFR, & The Fed’s Changing Framework

Repo, SOFR and the Fed’s changing framework collide causing disruptions in the Repo markets. With the heightened events over the past few weeks in the US funding markets, Federal Reserve policy decisions and the discussion regarding imbalances between collateral, cash and regulatory change are no longer mutually exclusive events. In looking at Fed correspondence over the past year, this comes as no surprise yet to date a reactionary posture has been adopted. Let’s take a look at why the Repo markets are important to the broader financial markets, discuss the structural impediments that caused the recent issues and identify who benefits and who loses.

In a speech from May 4, 2018, “Liquidity Regulation and the Size of the Fed’s Balance Sheet”, Vice Chairman for Supervision Randal K. Quarles offered his closing remarks:

“The final and most general point is simply to underscore the premise with which I began these remarks: Financial regulation and monetary policy are, in important respects, connected. Thus, it will always be important for the Federal Reserve to maintain its integral role in the regulation of the financial system, not only for the visibility this provides into the economy, but precisely in order to calibrate the sorts of relationships we have been talking about today.”

Let’s start by reviewing some basics:

What is a Repurchase Agreement?

A repurchase agreement, or Repo, is an agreement between a buyer and seller in which the buyer agrees to buy securities from a seller for cash, selling them back at a specified later date. Repurchase agreements are like collateralized loans where the value of the collateral is typically above the cash amount that is borrowed. In most cases, Repo agreements are over-collateralized. Cash providers in repurchase agreements typically include money market funds, insurance companies, corporations, municipalities, central banks and commercial banks that have excess cash to invest. Conversely, dealers and depository institutions rely on borrowing cash against long positions in securities to finance their net inventory and balance sheet positions, creating a link between rates in the fed funds market and those in secured short-term money markets.

What is the Secured Overnight Financing Rate (SOFR)?

In mid-2017, the Alternative Reference Rates Committee (ARRC) endorsed SOFR (Secured Overnight Financing Rate), as the preferred rate to replace Libor. SOFR is now being published daily by the Federal Reserve Bank.

SOFR is intended to be a broad and directly observable measure of the cost to borrow cash overnight and collateralized by Treasury securities through repurchase agreements. The general collateral repo (GC) repo market is what keeps the US government securities market functioning daily.

In choosing SOFR as the preferred choice to replace Libor, the regulators were seeking an index that was fully transaction based, included a robust underlying market covering broader segments of the repo market (Tri-party + cleared FICC bilateral repo) and a rate that correlated with other money market indexes (EFF, Overnight Bank Funding Rate, IOER and Tri-Party GC).

Libor currently references some $200 trillion worth of financial contracts across Derivatives, Loans, Securities, Mortgages and Business and Consumer Loans. Given the sheer nature, size and complexity of the market in conjunction with an impending 2021 phase out target date, the behavior of the Repo market will continue to grow in significance for the end-use Libor community as we move closer to the proposed 2021 deadlines.

https://www.newyorkfed.org/medialibrary/Microsites/arrc/files/ARRC-faq.pdf

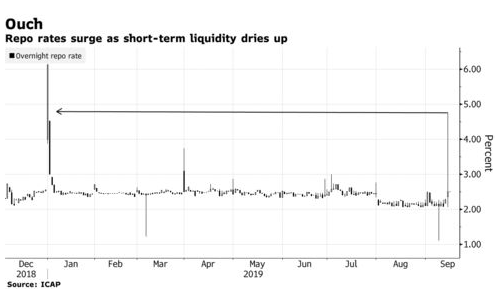

What Happened Recently with Repo?

In the middle of September, the Repo market experienced a sharp and unexpected spike in short term financing rates. Although some of the events which caused the short term cash squeeze were known (settlement of recent long end Treasury supply, corporate tax needs impacting money market funds and short-end Treasury supply counter to historical seasonal activity), the addition of the unexpected Saudi attack and the likely short-term need for additional USD drove an extended need for cash within the US banking system.

Although the confluence of events was unfortunate, the recent spike in Repo rates exploited several aspects of monetary, regulatory and fiscal policy, highlighting the need for change on the part of the current Fed framework to address the changing landscape and variables impacting an otherwise normal and safely functioning market. Many of these issues have been known and the direct result of policies adopted over the past 10 years either directly from the US government or Federal Reserve.

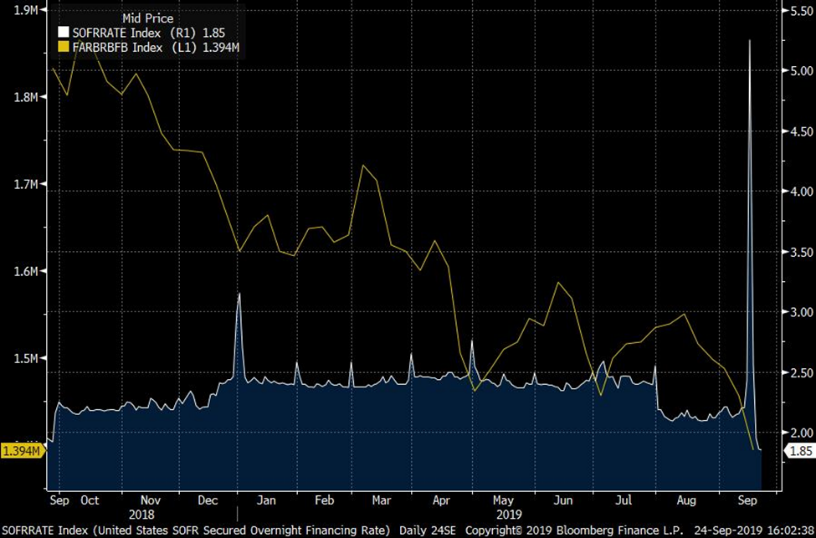

Perhaps even more importantly, with the Fed now publishing SOFR on a regular basis, and several firms involved in the issuance of SOFR-linked debt, the recent spike in Repo rates did not go unnoticed by the current Libor end-user. Since the underpinnings of the SOFR setting lies within the broader Repo market, short term spikes in the secured US funding markets have a direct impact on SOFR levels.

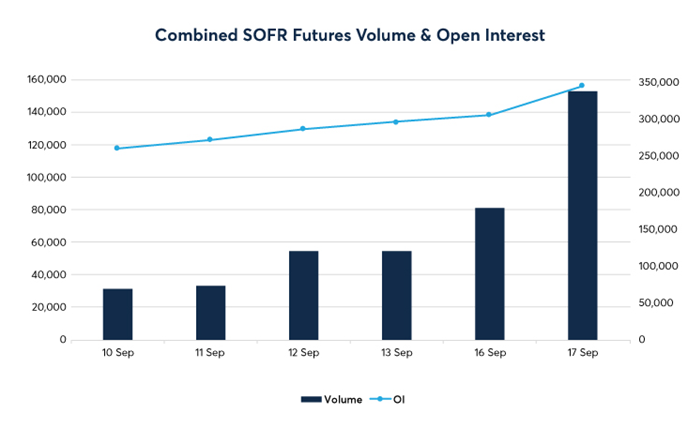

The chart below highlights the increase in trading volumes for SOFR off the back of the recent Repo distortions.

Chart below shows the recent spike in SOFR in conjunction with the decline in Excess Bank Reserves

The FED: A Switch to a Floor System & Ample Reserves

Prior to 2008, the Fed operated monetary policy under a ‘corridor’ framework and with a much smaller balance sheet than today (roughly $925 billion). Under the corridor system, there would be an upper and lower bound for the unsecured Fed Funds rate with the upper bound being the discount rate that banks could borrow from at punitive levels, with the lower bound being zero. Since the Fed did not pay interest on excess beyond required reserves, they were typically lent overnight in the Fed Funds market.

Unlike today, pre-GFC the Fed Funds market was an actively traded market. And like activity we are seeing from the Fed over the past few weeks to quell recent Repo distortions, the Fed would use Temporary Open Market Operations (TOMO) with day-to-day intervention to keep the Fed Funds rate within its target adjusting the reserve levels. The financial arbitrage between secured and unsecured was less than perfect, and like distortions seen today, the target level and trading level for Fed Funds varied from time to time.

In the period following the GFC, the Fed embarked on a program of Quantitative Easing, ensuring that the Banks had excess cash on hand to weather the crisis: beyond what was required. In this process, the Fed moved away from the corridor system on monetary policy, shifting to what is referred to as a ‘floor system” with the utilization of ample reserves.

In 2008, Congress gave the Federal Reserve legal authority to begin paying interest on required and excess reserves. In this process, the Fed moved away from the use of daily Repo operations to influence the Fed Funds rate, rather using the interest it would pay on excess reserves (IOER). The idea being this: banks would have no incentive to lend in the Fed Funds market to other banks for ‘less’ than what could be earned by keeping money simply parked at the Federal Reserve. Thus, the naming of this methodology as the floor system. As the IOER rate moved higher through normalization, so too would the Funds rate.

The Fed’s Balance Sheet, USD Demand & Imbalances

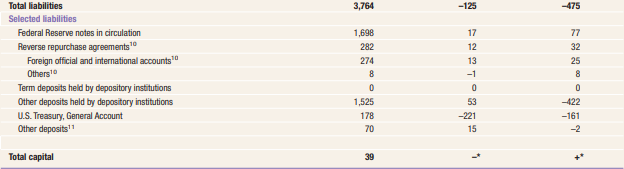

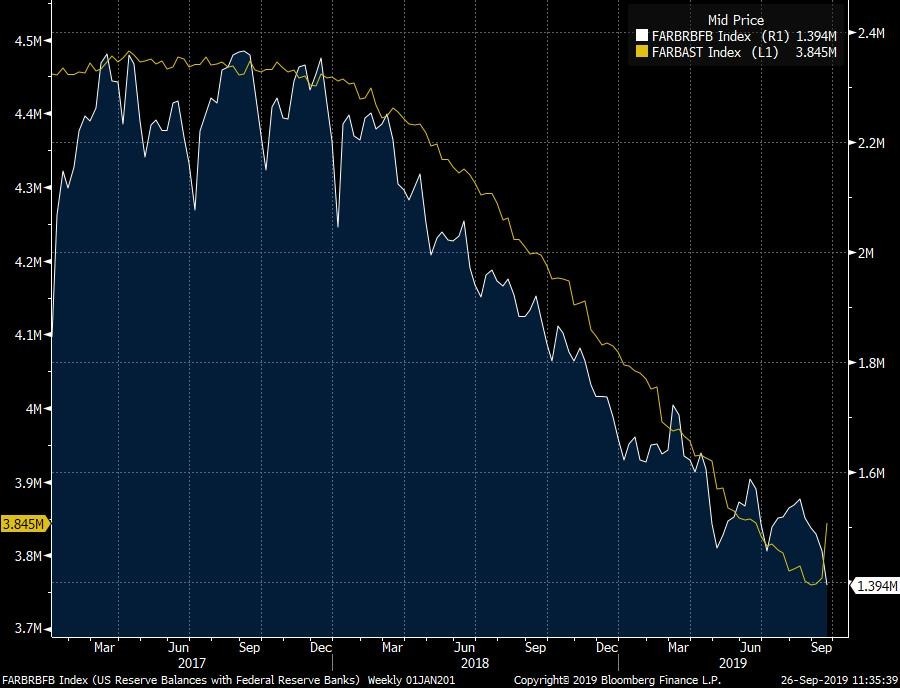

As the Fed has been shrinking its balance sheet up until late, bank reserves have been declining. In conjunction with this, currency in circulation grows over time as the economy grows. And the USD has never been in greater demand with the global economy at its weakest point since 2015-2016. Since the GFC, currency in circulation has more than doubled, from roughly $800 million to $1.7 billion. Additionally, by using Foreign Reverse Repo facilities, foreign official and international accounts have grown the Fed’s liability account by over $200 billion as foreign entities take advantage of cash collateral imbalances abroad.

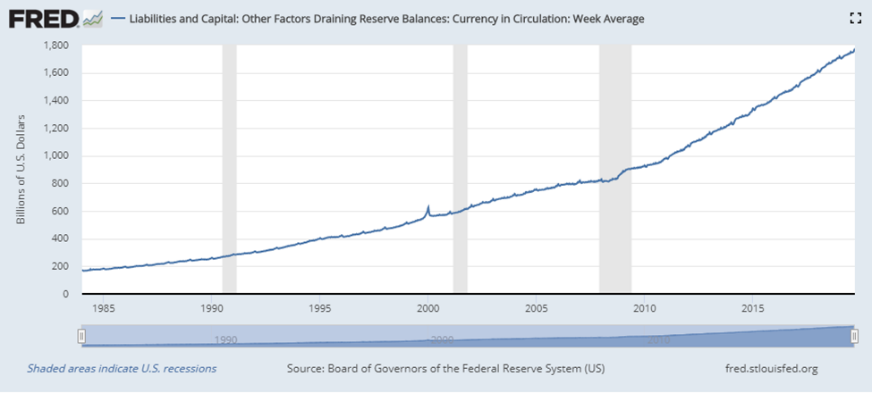

Demand for USD Growing Since the GFC: US Currency in Circulation

Recent Chart: Fed’s Balance Sheet Versus Decline in Excess Reserves

Continuous USD Demand

The demand for the USD has been consistent for most of 2018-2019. At the same time, the Fed was tightening for most of 2018 while simultaneously shrinking its balance sheet. Currency values don’t always adjust purely because of interest rate differentials. In this latest pocket of time, despite the Fed pivot and subsequent easing campaign, on a relative basis the funding differential between owning USD versus a pool of flat to negative yields is still significant. And the USD continues to strengthen, approaching levels last seen in 2015-2016. Relative to our global peers, the US economy remains on strong.

10-year chart on USD Index shows levels similar to 2015-2016

Why Aren’t the USD Being Released?

Bank’s desire to hold reserves has increased. Since the GFC, the Dodd-Frank Act and other regulations have increased bank’s capital and liquidity requirements. Essentially, banks are now required to maintain larger cash buffers to protect against shocks like the one that happened in 2008. According to the New York Federal Reserve, minimum reserve balances required for the eight largest US banks to meet liquidity needs during a banking crisis on any single day could be close to $1 trillion.

Reserves maintained at the Federal reserve are the bank’s main source of cash. So the demand for cash on hand at the largest banks is as high as its ever been.

Additionally, the need for High Quality Liquid Assets (HQLA), stress testing, living wills and resolution planning have further favored the use of excess reserves (cash) over Treasuries from a regulatory perspective. This occurred as dealer balance sheets remained high while the US government runs pro-cyclical deficits to the tune of close to $1 trillion per year with expectations of that pace continuing going forward. Recent bank surveys have all pointed toward a preference for the use of excess reserves to satisfy regulatory requirement.

Where Does the Recent Confluence of Events Around the Repo Market Leave the Fed?

“We look at this current window of time as offering three distinct, yet very related buckets for the Fed”:

1) The trigger (Events all requiring cash out. Some events were known, some weren’t. See our reference to this above)- increase balance sheet buffer.

2) The lack of response (regulatory bias holding back cash)- Powell backed away from this when questioned at the September meeting regarding the liquidity ratios. His response at the September press conference was clear: leave regulatory alone, increase reserves.

3) Market structure (Concentration of Cash). Top 8 banks hold majority of the reserves. Structural facility, broader market accommodation.

What Options Are Being Discussed to Address Recent Funding Concerns?

OUTRIGHT BALANCE SHEET EXPANSION- INCREASE OVERALL RESERVE BUFFER

As part of the way forward, we do think the Fed needs to increase the balance sheet, but with focus on the very short-end and consistent with their easing stance. UST paper 1-year and under.

“It’s more important for the Fed to stabilize the short term US funding markets at current levels than provide the market with another 25-basis point cut”- we are not suggesting the Fed won’t cut this month, but the more important issue here is the underlying money markets supporting the funding of the US government.”

Chart below: Fed balance sheet, excess reserves, SOFR and currency in circulation. Through $4 billion in balance sheet and $1.75 in excess reserves, the market began showing signs of stress. The average month-end spike in SOFR for 2018 was roughly 6-basis points. For 2019, that same month-end spike averaged 16-basis points.

We would look for a balance sheet adjustment of at least $250 billion to start. The discussion beyond the balance sheet, though, will need to incorporate regulatory and structural changes. But we don’t see the regulatory discussion as front and center in the next few months.

Standing Repurchase Facility

The Federal Reserve from the June Meeting:

“In their discussion of key objectives for establishing a repo facility, some participants raised questions about whether such a facility is needed in an ample-reserves framework, noting that the current ample-reserves regime has provided good interest rate control.”

Good Interest Rate Control?

“The Fed’s mandate, though, is increasing aggregate reserves. ‘Where’ those reserves end up, and why, matters. So should the Fed expand the reserve pool the discussion needs to be broader and more explicit.” Creating more money is the easy part for the Fed, yet the proper flow of cash versus collateral is necessary for efficient markets.

Excerpts from the Fed Minutes (June 18-19, 2019)

“The staff briefed the Committee on the possible role of a standing fixed-rate repurchase agreement (repo) facility as part of the monetary policy implementation framework; a facility of this type would allow counterparties to obtain temporary liquidity at a fixed rate of interest through repurchase transactions with the Federal Reserve involving their holdings of select securities eligible for open market operations.” The staff presentation noted how such a facility could provide a backstop against unusual spikes in the federal funds rate and other money market rates and might also provide incentives for banks to shift the composition of their portfolios of liquid assets away from reserves and toward high-quality securities.

Key design features for such a facility, including the fixed rate offered to counterparties, the set of eligible counterparties, and the range of securities eligible to be placed at the facility, would influence the effectiveness of a facility in achieving either of these objectives. The staff noted a number of considerations that could arise in setting these design parameters, including potential repercussions in unsecured and secured funding markets, the eligibility of counterparties in weak financial condition, the potential that turning to such a facility could become stigmatized, and issues of a level playing field across different classes of counterparties.

Participants commented on several issues in connection with key design parameters for a repo facility. In terms of the setting of the facility’s fixed rate, many participants acknowledged a tradeoff in determining the level of the rate relative to other money market rates. On the one hand, establishing the rate at a narrow spread above money market rates would likely provide better interest rate control and could also be helpful in avoiding stigma that can be associated with the use of standing lending facilities with fixed rates set well above the level of money market rates. On the other hand, setting the rate close to the level of money market rates could result in very sizable Federal Reserve operations daily that could be viewed as disintermediating the activity of private entities in money markets.

In considering the eligible set of counterparties for a repo facility, a number of participants noted that making the facility available only to primary dealers would likely imply that the effects of the facility would be most direct on repo markets, while the influence on the federal funds market would be only indirect. A couple of participants noted that, particularly if banks were eligible counterparties, it would be important for counterparties of all sizes to have access to funding through the facility on the same terms. A few participants noted that a facility could enhance financial stability by providing a means by which nonbank counterparties can readily obtain liquidity against their high-quality assets.

More Direct Emphasis on Repo/SOFR

As we referenced before, with the evolution of the new Fed framework post-GFC, the actual Fed Funds market is tiny now in comparison to the Repo and proposed SOFR market. And the potential conversion of a $200 trillion-dollar market brings systemic risk without unnecessary disruptions.

The success of SOFR over time is very dependent on the stability of the Repo market. Granted, small variances and market pressure around month and year-end is to be expected. And are largely insignificant with an averaging calculation. But extreme market dislocations in times of seemingly normal market conditions is not acceptable and will continue to add to the chorus of criticism of SOFR as a benchmark replacement from current Libor end users. The Fed needs to address this more specifically with policy.