The Most Powerful Buyers in Treasuries Are All Bailing at Once

- Fed, foreign governments, commercial banks all stepping back

- More pain for bond investors may be in store amid buyer void

By: Liz McCormick, Garfield Clinton Reynolds, and Michael Mackenzie

Everywhere you turn, the biggest players in the $23.7 trillion US Treasuries market are in retreat.

From Japanese pensions and life insurers to foreign governments and US commercial banks, where once they were lining up to get their hands on US government debt, most have now stepped away. And then there’s the Federal Reserve, which a few weeks ago upped the pace that it plans to offload Treasuries from its balance sheet to $60 billion a month.

If one or two of these usually steadfast sources of demand were bailing, the impact, while noticeable, would likely be little cause for alarm. But for every one of them to pull back is an undeniable source of concern, especially coming on the heels of the unprecedented volatility, deteriorating liquidity and weak auctions of recent months.

The upshot, according to market watchers, is that even with Treasuries tumbling the most since at least the early 1970s this year, more pain may be in store until new, consistent sources of demand emerge. It’s also bad news for US taxpayers, who will ultimately have to foot the bill for higher borrowing costs.

“We need to find a new marginal buyer of Treasuries as central banks and banks overall are exiting stage left,” said Glen Capelo, who spent more than three decades on Wall Street bond-trading desks and is now a managing director at Mischler Financial. “It’s still not clear yet who that will be, but we know they’re going to be a lot more price sensitive.”

Treasuries dropped again on Tuesday in Asia. The yield on 30-year US bonds jumped nine basis points to 3.94%, the highest since 2014, while that on 10-year notes climbed seven basis points to 3.95%.

To be sure, many have predicted Treasury-market routs over the past decade, only for buyers (and central bankers) to swoop in and support the market. Indeed, should the Fed pivot away from its hawkish policy tilt as some are wagering, the brief rally in Treasuries last week may be just the beginning.

Analysts and investors say that with the fastest inflation in decades hamstringing the ability of officials to loosen policy in the near term, this time is likely to be much different.

‘Massive Premium’

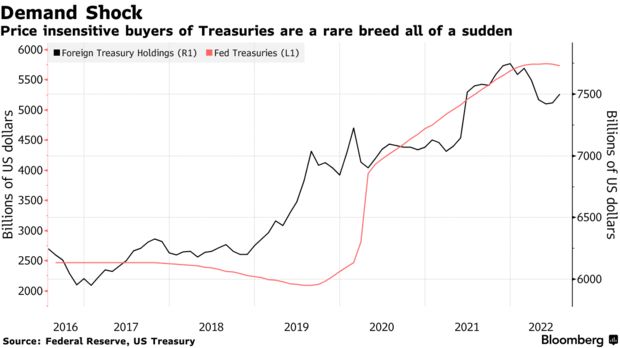

The Fed, unsurprisingly, represents the largest loss of demand. The central bank more than doubled it’s debt portfolio in the two years through early 2022, to in excess of $8 trillion.

The sum, which includes mortgage-backed securities, may fall to $5.9 trillion by mid-2025 if officials stick with their current roll-off plans, Fed estimates show.

While most would agree that lessening the central bank’s market-distorting influence is healthy in the long run, it nonetheless is a stark reversal for investors who have grown accustomed to the Fed’s outsized presence.

“Since the year 2000, there has always been a big central bank on the margin buying a lot of Treasuries,” Credit Suisse Group AG’s Zoltan Pozsar said during a recent live episode of Bloomberg’s Odd Lots podcast.

Now “we’re basically expecting the private sector to step in instead of the public sector, in a period where inflation is as uncertain as it has ever been,” Pozsar said. “We’re asking the private sector to take down all these Treasuries that we are going to push back into the system, without a glitch, and without a massive premium.”

Still, if it was just the Fed — with its long-telegraphed balance-sheet runoff — reversing course, market angst would be much more limited.

It’s not.

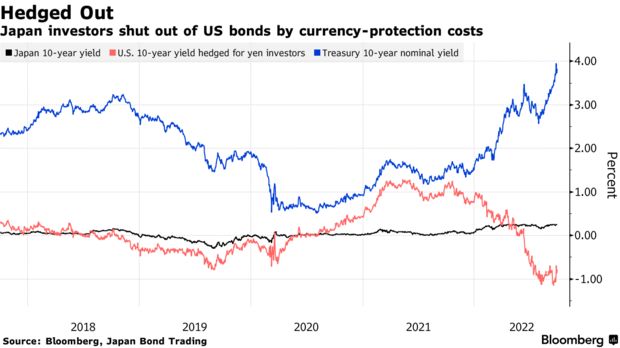

Prohibitively steep hedging costs have essentially frozen Tokyo’s giant pension and life insurance companies out of the Treasury market as well. Yields on US 10-year notes have slumped well below zero for Japanese buyers who pay to eliminate currency fluctuations from their returns, even as nominal rates have jumped above 4%.

Hedging costs have surged in tandem with the dollar, which has climbed more than 25% this year versus the yen, the most in data compiled by Bloomberg going back to 1972.

As the Fed has continued to boost rates to tame inflation in excess of 8%, Japan in September intervened to support its currency for the first time since 1998, raising speculation the country may need to start selling its hoard of Treasuries to further prop up the yen.

And it’s not just Japan. Countries around the world have been running down their foreign-exchange reserves to defend their currencies against the surging dollar in recent months.

Emerging-market central banks have trimmed their stockpiles by $300 billion this year, International Monetary Fund data show.

That means limited demand at best from a group of price-insensitive investors that traditionally put about 60% or more of their reserves into US dollar investments.

Peter Boockvar, chief investment officer at Bleakley Financial Group, said Monday it’s dangerous to just assume that the US Treasury will “ultimately find buyers to take the place of the Fed, foreigners and the banks.”

Citigroup Inc. flagged concern that the drop in foreign central bank holdings may set off fresh turmoil, including the potential for so-called value-at-risk shocks when sudden market losses force investors to rapidly liquidate positions.

Investors should bet on a drop in swap spreads “to position for continued CB selling and for further dash-for-cash style liquidity events,” Jason Williams, a Citigroup strategist, wrote in a report. VaR-shock-type events are more likely “given Fed risks are still pointed hawkish,” according to the report.

Banks Bail

Over the past decade, when one or two key buyers of Treasuries has seemingly backed away, others have been there to pick up the slack.

That’s not what’s occurring this go around, according to JPMorgan Chase & Co. strategist Jay Barry.

Demand from US commercial banks has dissipated as Fed policy tightening drains reserves out of the financial system. In the second quarter, banks purchased the least amount of Treasuries since the final three months of 2020, Barry wrote in a report last month.

“The drop in bank demand has been stunning,” he said. “As deposit growth has slowed sharply, this has reduced bank demand for Treasuries, particularly as the duration of their assets have extended sharply this year.”

It all adds up to a bearish undertone for rates, Barry said.

The Bloomberg US Treasury Total Return Index has lost about 13% this year, almost four times as much as in 2009, the worst full year result on record for the gauge since its 1973 inception.

Yet as the structural support for Treasuries gives way, others have stepped in to pick up the slack, albeit at higher rates. “Households,” a catch-all group that includes US hedge funds, saw the biggest jump in second-quarter Treasury holdings among investor types tracked by the Fed.

Some see good reason for private investors to find Treasuries attractive now, especially given the risk of Fed policy tightening tipping the US into a recession, and with yields at multidecade highs.

“The market is still trying to evolve and figure out who these new end buyers are going to be,” said Gregory Faranello, Head of U.S. Rates Trading & Strategy for AmeriVet Securities. “Ultimately I think it’s going to be domestic accounts, because interest rates are moving to a point where they’re going to be very attractive.”

John Madziyire, a portfolio manager at Vanguard Group Inc., said large pools of excess savings held at US banks earning next to nothing will prompt “people to shift into the short-end of the Treasury market.”

“Valuations are good with the Fed getting closer to the end of its current hiking cycle,” Madziyire said. “The question is whether you are willing to take duration risk now or stay in the front-end until the Fed reaches its policy peak.”

Still, most see the backdrop favoring higher yields and a more turbulent market. A measure of debt-market volatility surged in September to the highest level since the global financial crisis, while a gauge of market depth recently hit the worst level since the onset of the pandemic.

“The Fed and other central banks had for years been the ones suppressing volatility, and now they’re actually the ones creating it,” Mischler’s Capelo said.

— With assistance by Edward Bolingbroke