‘Bad’ central-bank policies and high inflation collide to create first bear market for global bonds in a generation

By: Vivien Lou Chen

Global bonds are in their first bear market of the past 30 years — a product of the relatively swift climb in interest rates backed by inflation-fighting central bankers across much of the world, which is reversing more than a decade of easy-monetary stances.

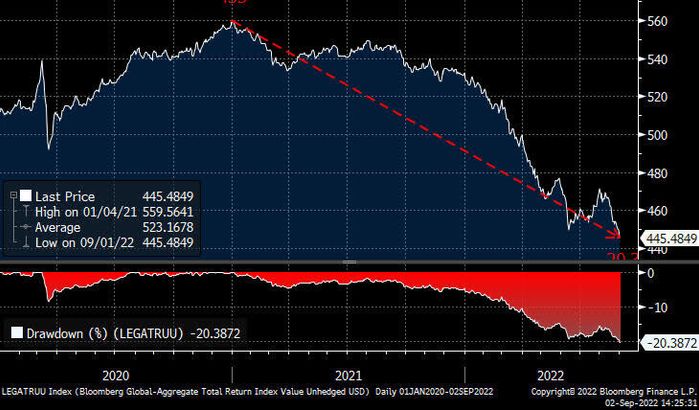

Persistently high inflation, unleashed by the COVID-19 pandemic around the world, is the biggest reason why the ordinarily safe sector of fixed income has fallen into such a rut. The Bloomberg Global Aggregate Total Return Index is 20% off its 2021 peak. Meanwhile, European government bonds just had their worst month on record, according to Mark Haefele, chief investment officer at UBS Global Wealth Management.

Most major central banks, with the exception of Japan’s, are being pressured to lift borrowing costs with speed: Wall Street’s biggest banks expect the European Central Bank to hike rates next week by an aggressive 75 basis points, while the Bank of Canada delivered a surprise 100-basis point hike in July and is anticipated to push borrowing costs into restrictive territory soon. In the U.S., policy makers have already delivered two 75-basis-point hikes and traders see a better-than-not chance of a third on Sept. 21.

Higher policy rates, in conjunction with this year’s rising market-based nominal and inflation-adjusted yields, pressure equity markets because investors rely on rates to determine the value of risk assets across the globe. What’s more, central banks are not yet done with their campaign of higher rates, creating continued turmoil across assets.

“We got to this point through bad central-bank policy over multiple decades,” said Gregory Faranello, Head of U.S. Rates at broker-dealer AmeriVet Securities in New York. “It’s a global phenomenon, not just in the U.S. We’ve had negative interest-rate policy in Europe for a long time and a lot of central banks buying negative-yielding assets. And that’s collided with an inflation environment we haven’t seen in a very long time. That collision happened very abruptly and is being exacerbated by the war in Ukraine, creating a once-in-a-lifetime turn in inflation.”

Bonds are the asset class that gets hit hardest by inflation, which eats into investors’ fixed returns. As investors sell off bonds, their prices drop and yields go higher. The policy-sensitive 2-year Treasury yield TMUBMUSD02Y, 3.548%, for example, is not far from its 15-year high. The 10-year yield TMUBMUSD10Y, 3.308% is up by 156.2 basis points from its January low, while the 30-year rate TMUBMUSD30Y, 3.460% is up by 132.7 basis points as of Friday.

The Bloomberg Global Aggregate Total Return Index, which includes government and investment-grade corporate bonds, has dropped 20% from its peak, the biggest drawdown since its inception in 1990. That meets the definition of a bear market, which is usually seen as a loss of at least 20% from a previous peak.

“Central bank policies were not aligned with an environment where inflation would rear its head as significantly as it has, and that in itself has caught the bond market off guard,” AmeriVet’s Faranello said via phone on Friday.

“Had policies been more aligned with economic fundamentals over time and this inflation pocket hit, we wouldn’t see the level or magnitude of what we’re seeing now,” he said. “When central banks increase rates this dramatically, it certainly has a very profound impact on how risk assets are valued, and we have seen a fairly decent repricing of risk assets just on interest rates moving the way they have.”

U.S. stocks have already suffered in 2022, with the large-cap benchmark S&P 500 SPX, 1.10% tumbling into a bear market as Federal Reserve officials lifted the target on their main policy rate to a range between 2.25% and 2.5% from almost zero. Dow industrials DJIA, 0.82% dropped by almost 5,563 points, or 15.3%, over the first two quarters, the worst performance since the U.S. outbreak of COVID-19 in early 2020, while the S&P 500 dropped 20.6% in the first half and Nasdaq Composite COMP, 1.60% fell 29.5% during the same period.

On Friday, all three major indexes finished lower for a third straight week after giving up the initial gains that following the August U.S. jobs report. Fed-funds futures traders see a 46% chance that policy makers lift rates to between 3.5% to 3.75%, and a 45% likelihood of them getting to between 3.75% and 4%, by December.

The past year’s selloff in bonds has been offset, from time to time, by continued interest from buyers, despite the risk of higher rates and a slowdown in economic growth. That was the case on Friday with Treasurys, which remain an investment of choice for many investors, particularly with 6-month through 30-year yields all still above 3%.

The next set of questions for traders and investors will be how much further central bankers will go from here, how long they’ll keep rates high, and how much borrowing costs will continue to affect the cost of capital and undermine the performance of risk assets.

Those hurt the most by the bear market in global bonds are investors who “have been investing in fixed income structurally, and were forced to buy negative-yielding debt,” said Faranello, a trader and strategist. “But the yield environment for investors who have been patiently sitting on the sidelines is a very good opportunity to get involved.”

Indeed, UBS Global Wealth’s Haefele said in a note that while “bonds have not been a great diversifier this year, prospects look better from here.”

“History suggests that fixed income is set to resume its traditional role as a diversifier,” Haefele said. In addition, “we have seen a number of private-equity managers taking advantage of the recent market correction in public markets to take companies private.”

“While the combination of falling bonds and equities can be disorienting for investors, we advise against sitting on the sidelines,” he said. “By being active and selective, investors can both improve diversification and set up a portfolio for longer-term gains.”