Bond Traders Wait for Calm to Shatter With Fed ‘Breaking Stuff’

By: Liz McCormick and Michael Mackenzie

Bond traders are taking little solace in the market’s recent calm for a simple reason: It’s not likely to last.

Two-year US Treasury yields, some of the most sensitive to expected changes in interest-rates, held in a relatively narrow range during the past week’s trading sessions, marking a reprieve from the volatility that erupted after Silicon Valley Bank’s collapse set off fears of a banking crisis.

But the cross currents that have cast uncertainty over the market haven’t gone away. Traders have dialed up bets that the Fed could raise interest rates in both May and June, threatening to delay the central bank’s long-awaited pause. Angst is building that a political fight in Washington over the debt limit may not be resolved until the government’s on the cusp of a default. And the economic outlook has been muddied by the prospect that banks will dial back lending to bolster investors’ confidence.

“The volatility has really been in the two-year note and it’s a function of the fact that the Fed and other central banks are breaking stuff,” said Gregory Faranello, Head of US Rates Trading and Strategy for AmeriVet Securities. “The Fed is trying to separate financial stability in the system and monetary policy — and I think that collides in May.”

“I also really have the debt limit on my radar,” he added.

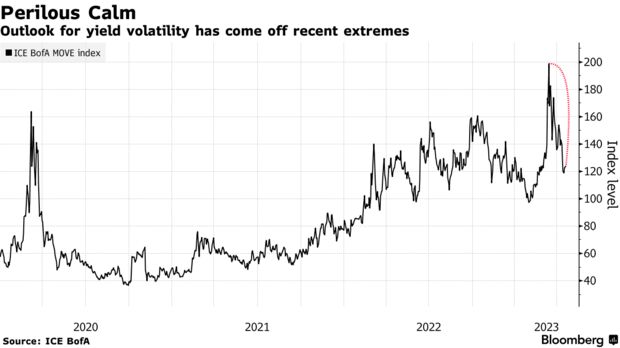

The ICE BofA MOVE Index, which tracks expected swings in Treasuries as measured by one-month options, has tumbled nearly 40% since mid-March, when it hit the highest since 2008. This week, two-year Treasury yields, which swung from as much as 5.08% to as little as 3.55% in March, ended at just below 4.2%, up slightly on the week.

Even so, swaps traders have ratcheted up the odds to about 20% that the Fed will follow a quarter-point hike in May with another such move in June. The reason: the economy is so far proving resilient and inflation seems still far from receding rapidly back to the central bank’s 2% target.

The coming week will provide fresh insight into how much more work policymakers have to do to rein in price pressures with the release of the personal-consumption expenditures index, the Fed’s preferred inflation gauge. The median estimate of economists surveyed by Bloomberg is for the measure to have slowed in March to a 4.1% annual pace from 5% a month earlier. There won’t be any fresh public comments from Fed policymakers because officials are in their customary blackout period ahead of their May 2-3 meeting.

While fear of a full-fledged banking crisis has ebbed since last month, the tightened credit conditions that have resulted are providing a headwind to growth. That has raised the specter of a slowly moving credit contraction that’s muddying the outlook for monetary policy and bond yields.

“Where our concern lies is around the potential for a credit crunch — to really put restraint on the consumer,” said Michelle Girard, head of US at NatWest Markets on Bloomberg television. “You have a whole host of data that can tell a bunch of different stories. So no one can be confident, the Fed included, on exactly what the path will be – or what other events may happen to alter expectations.”

While Girard expects a recession later this year as tighter monetary policy sinks in, she sees inflation staying over the Fed’s target, preventing them from cutting rates until 2024. That likely means 10-year Treasury yields “may take longer than some expect” to fall substantially further, given that swaps traders are still pricing in rate cuts later this year.

Benchmark 10-year yields trade just below 3.6% — down from as much as 4.1% this year and around 60 basis points less than those on 2-year notes. The gap has narrowed since reaching as much as minus 111 basis points on March 8 — the deepest inversion since the early 1980s — as the failure of SVB and two other lenders fanned recession fears.

Investors are on a “constant knife edge between recession and soft landing and everything in between,” said Gregory Peters, co-chief investment officer PGIM Fixed Income. “The tension point is such that you stay flat.”

— With assistance by Grant Hutchinson