Department of Defense Technology Investment Priorities

Executive Summary

The Office of Strategic Capital (OSC) is about 15 months old and recently released their FY24 Investment Strategy. Their goal: helping businesses manage long term risk using loans and guarantees. The strategy is facilitated by the Small Business Administration’s existing authorities and other authorities in current law. However, issues with DoD’s approach, how small businesses can address these very complex problems, and DoD’s own organizational conflicts must be addressed.

US Government Actions

On December 1st, 2022, the Office of the Secretary of Defense announced the establishment of the Office of Strategic Capital. According to the press release: “OSC will connect companies developing critical technologies vital to national security with capital. Critical technologies such as advanced materials, next-generation biotechnology, and quantum science often require long-term financing to bridge the gap between the laboratory and full-scale production, referred to as the “Valley of Death” in industry.”[1] The release broadly outlines an advisory council, mostly comprised of OSD leadership and aligned under the Under Secretary of Defense for Research and Engineering (OSD R&E) to complement other innovation organizations already executing programs to support critical technology developers. OSC will do this by “scaling” investments between pure S&T organizations like DARPA (Defense Advanced Research Projects Agency) and those more closely linked (at least in theory) to the production of technologies. The primary tools in OSC’s quiver are loans and loan guarantees for companies meeting some stringent criteria instead of grants or contracts more commonly used in acquisition.

Interestingly, this was preceded by a reorganization of R&E. In May 2022, R&E made several changes to the titles and underlying structure of their leadership team, renaming the Chief Technology Officers for Science and Technology (S&T), Critical Technologies (CT), and Mission Capabilities (MC). Insights into the underlying structure were advertised, but the link is not active, and no organization charts can be located on the DoD website. This makes finding the correct office problematic, and the relationship between OSC and the rest of R&E cloudy.[2]

By mid-2023 Congress made several statements calling the veracity of the office into question. In the budget request for 2024, the administration had not made any request for authorities for the $99 million that the new office would use to execute its mission, putting any funds at risk of cuts or reprogramming actions.

This started a long discussion between the administration and the four defense committees as staff on both sides tried to define what the White House really wanted accomplished.

Other members of congress expressed concern about OSC’s intent to use private consultants who also have portfolios as private defense consultants or work for defense companies. The potential conflict of interest seemed to be one cause for the hostility shown by several members.[3] The debate and discussions continued, with the result that Congress included the new office in the 2024 National Defense Authorization Act, section 903.

Mission

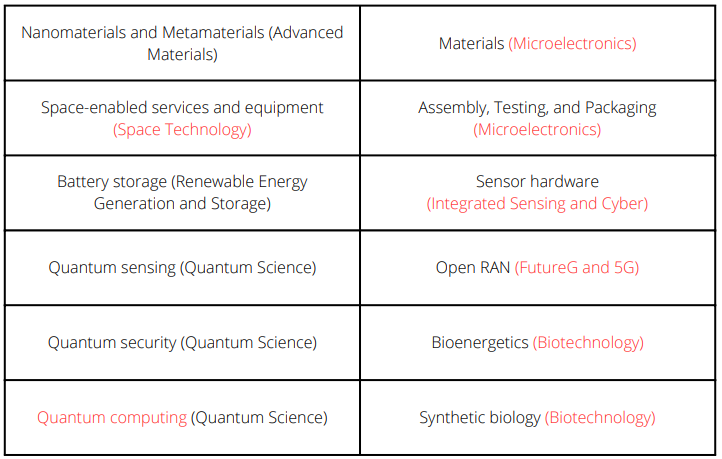

On March 8, 2024, a full 15 months after the first announcement, OSC published its Inaugural Investment Strategy. According to this document, the mission of OSC is to attract and scale private capital to technologies critical to the national security of the United States. “OSC’s initial emphasis is on using loans and loan guarantees in partnership with other federal departments and agencies to crowd in capital for component-level technologies.” (emphasis added) The initial priority areas listed in the

strategy are:

The concept is sound. Using taxpayer dollars, OSC will prioritize a technology, select the correct financial tools, and then evaluate if DoD or another federal agency should in fact execute the investment or if another federal agency should be the lead (or require deconfliction). Execution, however, may be more complex.

What Problem Does This Fix?

Often, new organizations are created because it seems like a good idea, or because a particular leader has a specific itch to scratch. In this case the problem DoD is attempting to solve is how to encourage investment when business makes decisions based on risk / return while DoD makes decisions based (hopefully) on battlefield effects and minimizing personnel risk. Some technologies must be invented, with considerable investment, and may not show any value in a reasonable time because the science is too ill-defined, the payback period is too long, or the transition from laboratory to production line (requiring a high level of quality to ensure adequate profit margins) is in doubt. The theory behind OSC is that the government would provide a loan or loan guarantee to industry to lessen risk and make the investment more attractive.

The OSC strategy is not, in fact, a strategy but a policy and process document. It lists methods and some decision criteria; but is more of a marketing brochure. OSC uses an example of a 2.5% investment being leveraged to allow the remaining 47.5% to be gained through the Department of the Treasury’s Small Business Administration’s (SBA) Small Business Investment Company.[4] OSC would have SBIC fill in 47.5% (as loans or guarantees) and the other 50% consisting of private funds. Department of Treasury funds, for DoD use, are in Treasury’s Department of Defense Credit Program Account. Although the NDAA does not specify the amounts in those accounts, it does authorize the OSC Director to use those funds for loans and loan guarantees that fall under Section 903. The result in the example is amazing…for only 2.5% of federal funds a project could be funded to solve these very difficult problems. No concrete examples are given, just what might be possible. Importantly, nowhere in the document does OSC discuss the fact that these projects will likely have a substantial failure rate. Technology invention resists timelines. Failure is a part of creation, and if only to manage expectations OSC should consider this in their communications.

However, there are issues with this approach. According to Section 903 (d) “In the case of an eligible investment made through a direct loan, not less than 80 percent of the total capital provided for the specific technology to be funded by the investment shall be derived from non-Federal sources as of the time of the investment.” That means private capital must be at least 80% of the total project and 20% may be from loans made by the USG, even though the SBIC program allows for matching ($1 of private capital gets up to $2 of debt from the Small Business Administration) for small businesses.[5] To be clear, SBIC loans are private equity from qualified investment institutions. For every $1 the fund raises from investors, SBA will commit up to $2 of debt, subject to a cap of $175 million. Using SBIC may be a way OSC can avoid Section 903 limitations, e.g., the 80% rule. This, however, has not been tested in practice. About a year ago, OSC announced their intent to sign a Memorandum of Agreement with the SBA to form a joint approach. As part of this agreement one of the four types of SBIC financial instruments, the Accrual Debenture, appears to be the only way to fund longer term (10 years with a possible extension of an additional five years) capital investments.[6] To date, no announcements of any agreements using this tool have been made by DoD.

Another issue is that the types of technologies DoD wants to mature require considerable technological and logistical depth. Major players like Lockheed Martin, Boeing, Raytheon Technologies, Northrop, and others may have the capabilities needed. However, to qualify for the SBIC in the OSC strategy, the company must qualify as a small business: Less than $24 million tangible net worth, average net income (after federal taxes) for the preceding two years of less than $8 million. There are ways around this as companies may elect to enter mentor protégé or joint venture arrangements in order to allow the small business to be the project “lead”. This adds a level of complexity to the agreement for both parties not only for financial matters but also for intellectual property concerns.

A final issue is an apparent conflict in responsibilities within OUSD R&E. In the reorganization mentioned above, the USD R&E and Assistant Secretary of Defense for Critical Technologies have responsibility for several areas that are also covered by OSD’s strategy (highlighted in RED above). Both the Deputy Chief Technology Officer for Critical Technologies and the Director OSC are direct reports for the Under Secretary R&E. In fact, the Secretary has 13 direct reports with the addition of OSC. This presents bureaucratic challenges as lanes intersect within OSD.

These clashes mean industry must be very knowledgeable about the overlaps and nuances between the offices and authorities for execution of programs. Making success more complex for industry instead of simpler is a detriment but can offer different approaches for industry. Traditional vehicles like cost plus incentive fee contracts, Material Transfer Agreements, Technical Assistance Agreements or Cooperative Research and Development Agreements[7] have been used to solve difficult technology problems in the past. Although contract vehicles seem to have more to do with recent popularity than with the problems to be solved (cost plus contracts have fallen out of favor in the past 15 years) they remain available options for the government to incentivize industry to invest in longer term, higher risk ventures to invent technologies and make them producible. OSC potentially gives industry more choices when considering a project for the USG.

Industry must be aware of the options with OSC (SBIC loan vehicles are the only example so far) as well as the duplicative areas of responsibility in OSD R&E for technology development and deployment. Navigating these approaches will add time and manpower resource requirements to the cost but may allow industry to be more discerning about which projects to pursue for a given risk equation.

Conclusion

In fairness, one of the most difficult tasks in our world is creating a new organization out of thin air and executing the mission while still building (hiring people, facilities etc.) and understanding the environment. It remains to be seen if OSC will create opportunities for government and industry to substantively advance the cause of technology development or only add to the already bloated bureaucracy of DoD. If the latter, Congress may have to step in and define roles and responsibilities for these offices to include addressing the span of control at the Under Secretary level. Industry’s feedback to DoD and Congress will be important as projects are considered and either accepted or rejected based not only on their merits but also on the difficulty of getting funding for the teams chartered with advancing our technological base. Interestingly, Section 903 sunsets OSC in 2028. This likely indicates that Congress has some skepticism about the value of this office, but they are willing to give the DoD some time to prove OSC’s worth due to the clear need for improvements in these technology areas.

Learn more about the author, Advisory Board member and retired U.S. Air Force Major General Michael Snodgrass.

[1] See: Secretary of Defense Establishes Office of Strategic Capital > U.S. Department of Defense > Release

[2] See: Organizational Improvements to the Office of the Under Secretary of Defense for Research and Engineering > U.S. Department of Defense > Release and the inactive link is: https://www.cto.mil/wp[1]content/uploads/2022/05/usdre_org_chart_09may2022_distro_a.pd

[3] See: Office of Strategic Capital hits road bumps on future funding (federalnewsnetwork.com)

[4] See: DOD, SBA ink new Small Business Investment Company agreement to support critical technology | DefenseScoop. The Small Business Administration already licenses and funds hundreds of SBIC companies, which currently manage over $37 billion in federal and private capital

[5] See: 2018 SBIC Program Overview.pdf (sba.gov)

[6] See: New DOD/SBA Initiative Builds Technology Critical to National Security – Lexology. It is interesting to note that the actual MOA cannot be located on any public or DoD website.

[7] See: TECH TRANSFER AGREEMENTS | U.S. Department of the Interior (doi.gov)